Hi Everyone,

I'm showing my age when I say I'm a fan of Data. Actually, I like data, too. Seriously, in follow up to Sudha's lecture on determinants of health, I wanted to provide a few additional resources for you.

For example, CDC offers the free software program

Epi Info version 7, an essential tool for public health practice. There is also

OpenEpi,

which is a free, online, multilingual, and open source software for epidemiologic statistics entry and calculation that is compatible with smartphones.

But if you want to know the basics of how to use these tools, the

CDC EXCITE program has a nice description of epidemiology fundamentals and a

step-by-step process for conducting an outbreak investigation as a disease detective.

|

| A WWII sign admonishing US soldiers to take their antimalarial medicine |

If you like mysteries and want to get some page turning epidemiological investigative texts, a must read classic in this genre is

Berton Roueche's "The Medical Detectives." A couple of more recent true tales are described by Richard Preston in his 1994 book

"The Hot Zone," about a hemorrhagic virus incident in Reston, VA, and his 2002 book

"The Demon in the Freezer," about the biological weapon agents smallpox and anthrax. Also, here is a

recent story from the BBC about current day detectives of exotic diseases.

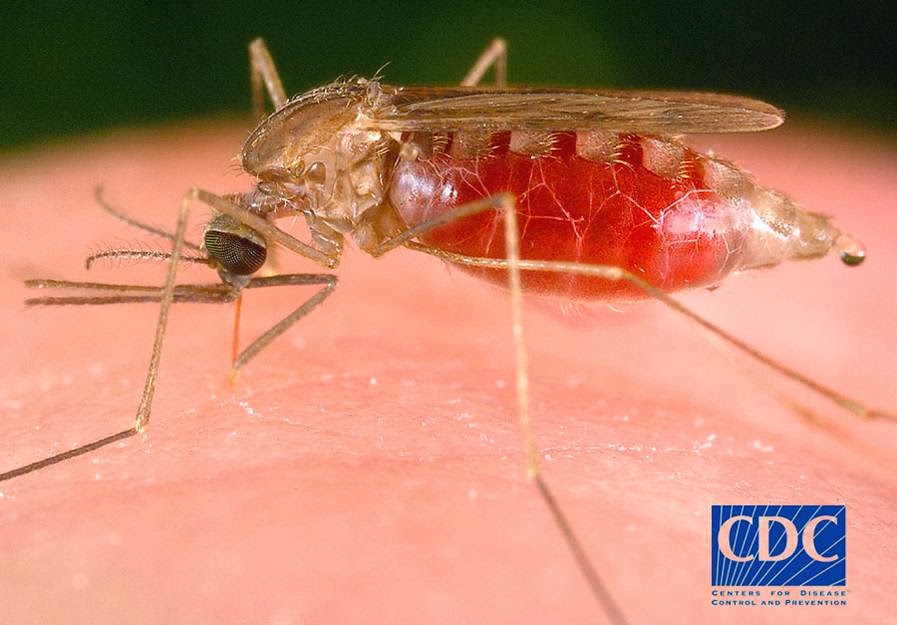

Lastly, here are links to two papers I published from my dissertation where I used the

cross-sectional survey method for assessing the US population's r

isk perceptions regarding ticks and Lyme disease and mosquito bites and viral encephalitis. I observed, among other things, that the majority of Americans (the survey sample size was representative of the US population) have misperceptions and inadequate knowledge regarding the safety and efficacy of

DEET-containing insect repellents, despite a nearly

40 year history of the product's positive safety record.

In terms of theory to guide the development of surveys, the theoretical basis I used was the Precaution Adoption Process, developed by Neil Weinstein et al, Rutgers University, which, simply stated, suggests that people decide to adopt a protective behavior based on the individual's perceived susceptibility to and severity of a hazard. The greater the perceived susceptibility and severity, the greater likelihood a precaution will be adopted by the individual. The lower the perceived susceptibility and severity, the less likelihood a precaution will be adopted by the individual. Maybe the skulls and Atabrine sign above is an attempt to change malaria prophylaxis behavior, i.e., you are susceptible and the severity is death?

For example, a hazard with low perceived susceptibility and severity is radon gas. It is odorless, tasteless, invisible, and produces a serious hazard, lung cancer, that may not be experienced for decades. Thus, taking a precaution to mitigate one's house against naturally occurring radon gas from underlying soil, by sealing cracks, installing a special ventilation system, etc., will usually be low, in a surveyed population.

What are other examples where you think the Precaution Adoption Process could be relevant in understanding health behavior or not applicable?

See you soon,

Jim

Hello Everyone,

Hello Everyone,